Non sono parenti, o almeno così parrebbe, anche se entrambi hanno origini irlandesi. Appartengono a epoche diverse, nati e vissuti in terre lontane, ma hanno lo stesso cognome, sono due grandissimi poeti animati da una profonda spiritualità e si somigliano persino fisicamente! In questo intensissimo testo, James scrive una lettera profonda e toccante al suo antenato poetico, Charles – che potrebbe essere anche un dialogo con sé stesso – ed ho pensato che, nel Giorno Internazionale della Poesia, non ci fosse nulla di più adatto a indicarne il ruolo di ponte fra tempi, luoghi ed anime. Un Poeta che parla con un altro Poeta nello spazio sublime e luminoso dello Spirito, dove il tempo non esiste e tutto è Uno.

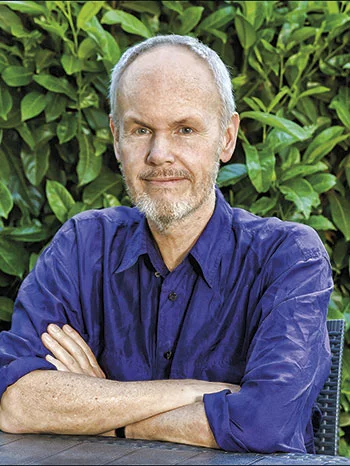

Charles Harpur (1813 – 1868) nacque a Windsor, New South Wales in Australia, da una famiglia originaria della contea di Cork in Irlanda, uno dei primi europei a nascere in quel paese. Suo padre era maestro di scuola, ma Charles ebbe la fortuna di avere a disposizione la vasta biblioteca del governatore e di una ricca famiglia del luogo. Di cultura vastissima, ma quasi del tutto autodidatta negli studi superiori, fu autore copiosissimo di poesie di straordinaria bellezza e raffinatezza, sulle bellezze selvagge della natura, sul mondo aborigeno, sulla teoria poetica e la natura umana. Dopo una serie di lavori precari, collaborazioni con giornali e riviste e come insegnante e direttore di un ufficio postale, si dedicò all’agricoltura, ma fu anche nominato commissario delle attività estrattive dell’oro. La morte del secondo figlio, Charles, dovuta a un colpo di fucile partito accidentalmente a Charles Harpur, lo prostrò a tal punto che non si riprese più e infine si ammalò di tubercolosi. Durante la sua vita pubblicò molto poco dei suoi oltre 700 testi poetici, ma dalla fine del 19° secolo e a tutt’oggi è riconosciuto come il poeta nazionale australiano e la sua fama è in costante crescita. È possibile che vi siano dei lontani legami di parentela con James Harpur, che, con Charles condivide incredibilmente un’ispirazione poetica fortemente spirituale e, ancor più incredibilmente, una certa somiglianza fisica? Chi lo sa? Quel che è certo è il legame ben più saldo di quello del sangue che li unisce.

FRANCESCA DIANO

N.B. Le parti in corsivo nel testo sono citazioni di versi di Charles Harpur.

Ringrazio l’editore Andrea Molesini per il testo, che è parte dell’antologia della poesia di James Harpur, Il vento e la creta, a cura di Francesca Diano, Molesini Editore, 2024.

*************************************

Lettera a Charles Harpur

a Charles Harpur

Caro Charles,

non mi sono mai spinto fino a Singleton,

a Jerry’s Palins o ad Eurobodalla,

la tua fattoria sopra il viottolo rialzato

con cigli erbosi ed eucalipti;

la tua tomba, e quella di Charles, tuo figlio

insieme incorporate presso la casa colonica.

Windsor l’ho vista, e invano ho cercato

di immaginarti ragazzo

da quel tuo dagerrotipo seppia –

come un vecchio soldato confederato,

barba fluente, biancogrigia,

sguardo sinistro da profeta Elia.

Accanto, il tuo amico, il fiume Hawkesbury,

che si snoda fra campi autunnali;

ed Omero che bisbigliava tra gli alberi –

i versi che più amo furono anche tuoi:

Come la genia degli uomini è quella delle foglie

alcune il vento ha disperse a terra, mentre altre

ancora spuntano sui rami fruttiferi,

per fiorire nella loro stagione. Così degli uomini

muoiono e si rinnovano le generazioni.

Hai scritto che, dopo che le alluvioni distrussero

la tua fattoria, il primo attacco di TBC

e la morte di Charles ti stroncarono.

Poi scrivesti il tuo proprio necrologio:

Qui giace Charles Harpur,

che a cinquant’anni

giunse alla conclusione

di vivere in un’epoca fasulla,

sotto un Governo fasullo,

e fra amici fasulli,

e che qualunque altro Mondo

dovrà essere dunque

un mondo migliore del loro…

A malapena sopporto il pensiero

del tuo purgatorio prima della morte,

all’appassire del tuo errante cercare

di trarre la verità dalla poesia

in un coraggioso e nuovo New South Wales

edificato dalla gentaglia del Vecchio Mondo

e dalle fustigazioni quotidiane: non meraviglia che tu veleggiassi

verso la piana nerovino di Troia

smistando lettere all’ufficio postale

o passassi quegli anni ad allevare pecore

per ricavarti del tempo per scrivere, per poi affrontare

la croce delle lettere di rifiuto.

Cosa ti ha sostenuto? La fede? O il timore

di incontrare Milton nell’aldilà?

O il magico ingresso delle idee

che apparivano come le tue oche in volo

che seguono il serpeggiare della valle, eppure

s’allargano in lunghezza e in alcuni luoghi

spesso si staccano in punti solitari.

O t’han rapito gli occhi della tua Musa –

due mezzenotti di pensiero appassionato –

che nella mente ti hanno acceso immagini,

come quella del granchio sulla spiaggia, che attende

la sua preda fra le pietre lavate dall’onda

scintillanti al sole – e si accende di luce

quando si muove, quasi il suo guscio umido

andasse in fiamme.

I tuoi genitori t’han portato sradicato

in una terra di grog e marsupiali.

Hai mai chiesto a tuo padre, Joseph,

della sua infanzia a Kinsale?

O ti sei mai orientato con racconti

delle tue tradizioni familiari, quali quelle ch’io udii –

come, al seguito di Richard de Clare,

noi Harpur arrivammo a Wexford?

O del viaggio della bara di tuo padre

a solcare i mari del sud, per unirsi

alla tribù di Sisifo e forgiare

l’Ade agli antipodi della Britannia?

Ma tu, per i tuoi sogni condannato

ad essere il poeta laureato della tua nazione,

hai deportato te stesso in un regno

al di là delle Montagne Azzurre

ed hai scoperto… non la “Cina” –

lo Shangri-La delle fantasie dei deportati –

ma un cielo all’alba, alberi umidi di rugiada

e tutti luccicanti d’un velato argento;

o la sinuosa vallata delle acque;

o ampi ardenti campi, lieti di grano.

Sapevi che la natura ha una sorgente sacra

così come il sole è la fonte della luce

ed hai cercato di aprire gli occhi alla gente.

Ma non videro altro che un folle di Dio,

una voce che condannava nel deserto,

sacerdozi che restringono l’anima

incline al bere, all’autocommiserazione – ma che vedeva

in profondità nella vita delle cose:

e quel che è profondo è sacro, e deve tendere

a un qualche fine divino universale.

Fasulli l’epoca, il governo, gli amici –

qualunque luogo tranne Eurobodalla

ti parve una benedizione alla fine.

Immagino la scena sul tuo letto di morte,

la spettrale figura della Disperazione,

a testa china, fintamente afflitta;

ma anche Mary, seduta lì accanto

a ricordare il tuo corteggiamento; e scaffali

di pagine non lette, ibernate

come alberi d’inverno, per riaprirsi

in qualche luogo in una futura primavera,

di nuovo verdeggianti.

***********************

Letter to Charles Harpur

i.m. Charles Harpur (1813-68)

For Kevin Brophy and Penelope Buckley

Dear Charles,

I never got as far as Singleton,

Jerry’s Plains, or Eurobodalla,

your farm above the banked lane

of grassy verges and eucalyptus;

your grave, and that of Charles, your son

embedded by the farmhouse.

I did see Windsor, and tried in vain

to imagine you as a youngster

from your sepia daguerrotype –

like an old Confederate soldier,

waterfall beard, greyish white,

the baleful stare of Elijah.

Nearby, your friend, the Hawkesbury,

uncoiled through autumn fields;

and Homer was whispering in the trees –

my favourite lines were yours as well:

‘The race of men is as the race of leaves:

some the winds shed upon the ground, while still

the fructifying boughs put others forth,

to flourish in their season. So of men

the generations die and are renewed.’

You wrote that after floods ruined

your farm, the first flush of TB,

and Charles’s death had broken you.

Then came your self-obituary:

‘Here lies Charles Harpur,

who at fifty years of age

came to the conclusion,

that he was living in a sham age,

under a sham Government,

and amongst sham friends,

and that any World whatever

must therefore be

a better world than theirs …’

I can hardly bear to think about

your purgatory before death,

the fading of your errant quest

to wrestle poetry from truth

in a brave new New South Wales

constructed by Old World gentry

and daily floggings; no wonder you’d sail

to the wine-dark plain of Troy

as you sorted letters in a post office

or spent those years farming sheep

to scrape the time to write, then face

ordeal by rejection slip.

What kept you going? Faith? Or fear

of meeting Milton in the afterlife?

Or the magical ingress of ideas

appearing like your ducks in flight

following the windings of the vale, and still

enlarging lengthwise, and in places too

oft breaking off into solitary dots.

Or were you rapt by your Muse’s eyes –

two midnights of passionate thought –

igniting images in your mind,

such as your beach crab, who waits

for his prey amid the wave-washed stones

that glisten to the sun – gleaming himself

whenever he moves, as if his wetted shell

were breaking into flame.

Your parents brought you rootless

into a land of grog and marsupials.

Did you ever ask your father, Joseph,

about his childhood in Kinsale?

Or orientate yourself with stories

of family lore, like those I heard –

how, in the wake of Richard de Clare,

we Harpurs came to Wexford?

Or of your father’s coffin-voyage

across the southern seas, to join

the tribe of Sisyphus and forge

the down-Underworld of Britain?

But you, convicted of your dream

to be the laureate of your nation,

transported yourself to a realm

beyond the Blue Mountains

and discovered … not ‘China’ –

the Shangri-La of convict fantasies –

but a dawn sky, trees moist with dew

and glinting all with a dim silveriness;

or the sinuous valley of the waters;

or wide warm fields, glad with corn.

You knew that nature had a sacred source

even as a sunbeam’s fountain is the sun

and tried to open people’s eyes.

But all they saw was a fool of God,

a voice de-crying in the wilderness,

soul-dwarfing priesthoods

and prone to drink, self-pity – yet seeing

deep down into the life of things:

and what is deep is holy, and must tend

to some divinely universal end.

Sham age, government, friends –

anywhere but Eurobodalla

seemed a blessing in the end.

I picture your deathbed tableau,

the spectral figure of Despair,

head bowed, pretending to grieve;

but Mary, too, sitting there

recalling your courtship; and shelves

of unread pages, hibernating

like winter trees, to open

somewhere in a future spring,

in leaf again.

(C)2024 by Francesca Diano RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA

Commenti recenti