Gilberto Rolla’s website https://gilbertorolla.wordpress.com/

I delivered this talk on the 29th of September at the 2018 International Poetry on the Lake Festival at Orta, Italy.

“All arts aim to the word, but the word to silence.”

Carlo Diano

The idea for this talk was inspired by Gilberto Rolla’s Casket Books (Libri Scrigno in Italian), objects d’art where the different techniques employed contribute to create unique works of very fine craftsmanship and suggestions. While I was exploring them, trying to decode the artist’s intentions and aims, I began reflecting on how often writing, sacred texts, literature, especially poetry, and visual arts, have walked side by side, enhancing each other or, better still, reciprocally highlighting some hidden sides and meanings. And, since their origin, books offered a perfect ground for this beautiful love dance.

We can go very far back in history and retrace illustrated books, as soon as something like what we now consider to be a book made its appearance in Western cultures. Before that, as far as we know, papyrus scrolls bore also images, usually of gods or connected to the divine, like the Egyptian Book of Dead. But, when books with vellum pages began to appear, their rarity, their preciousness and their extreme value, not just as fine objects, but for their holy content, required an adequate decoration to celebrate God’s glory. Let’s just think of the illuminated manuscripts, making their first appearance during the early Middle Ages: Gospels, Bibles, Psalters, Books of Hours and especially the Book of Kells.

But, before talking about that, let’s see what Rolla’s Casket Books are and how they originated. Gilberto Rolla is a renowned architect with a love for painting and drawing. In his lifelong activity, while restoring old or ancient buildings, he often happened to find a number of old books that had been left behind, perhaps because they were judged of little or no value after they had been read, or because they had been forgotten or discarded. But he has also rescued from the garbage plastic bags full of books that had been thrown away, whose sad final destiny was to be sent for pulping.

Loving everything connected to culture and knowledge – he had founded the International Book Centre in Pontremoli – he couldn’t help sparing them a sad, inglorious end and he started bringing them home. All book lovers feel that a book is a living thing, an entity, so they cringe at the idea of destroying a book, even an old and battered one. As the artist Brian Dettmer, who creates beautiful, amazing sculptures out of old books, says: “Books have the potential to continue to grow and to become new things, so they really are alive.”

At first Rolla didn’t actually know what to do with them, because they were often in poor conditions and of not great literary value. So, he just kept them. Then, one day in 1981, he got the idea of using one of those volumes as a protection for one recent and still wet China ink drawing, one of the very many small-sized drawings, watercolours, gouaches and sketches he had been made since the Seventies. These works represent landscapes, buildings, human figures, shadows, characters from classical mythology, or sometimes just suggestions, and actually they give the impression of a poet giving a visible form to his dreams and his visions.

So, what he did was to carve the text block in order to create a sort of niche, which would safely accommodate and protect his drawing. Now the book had changed its function and, from a support for and vehicle of words, had turned into the ideal housing for his works on paper. But the poor overall condition of the old books and their fragility were inadequate to last and to match the quality of their content, therefore he devised a way to transform the cover and indeed the whole body of the book, into a sturdy but very precious case.

Working with different kinds of glues he builds a solid case, which can still be opened like a book, but is not a book anymore, not in a traditional sense anyway. All its outer parts – front and back cover, spine, edges and text block – are then coated and sealed either with tar or gold paint and then varnished, while the inside is lined with paper and then one of his works is inserted and framed inside the niche thus obtained.

The patterned textures of the book covers are usually decorated by working the material as to create a sort of bas-relief, and by inserting some images coated with layers of resin, so as to obtain a glazed finish.

The idea of the tar finish, which creates a very shiny, thick, deep black surface, came to him by observing the practice of caulking fishing boats, as he has always lived near the sea and had been always fascinated by caulk’s texture and colour. The result is a kind of sculptured case, inside which his works are preserved.

The heavy, compact objects obtained through this long and meticulous work, which change in size and shape according to the original old book, has indeed all the characteristics of an ancient casket, apt to preserve and protect something precious. They actually remind me of foldable icons. And it is interesting to note that, in orthodox icons, a hollow space is carved into the wooden plate, in order to house and frame the actual painted icon, and this hollow space is actually called ‘casket’.

Written words though are not exiled from his Casket Books. Their original function as books is not betrayed. On the endpaper, along with some other smaller drawings or paintings he usually applies, Rolla writes in his elegant handwriting, some lines, or phrases or quotations inherent to the images, or some petite poème en prose, and the title he has devised for each Casket Book, thus actually baptizing it for the second time, giving it a new life. And everything – the surface’s texture and pattern, the front cover image, the handwritten texts, the title – is not only in harmony, but intimately interconnected with the work preserved inside. Indeed everything rotates around that image, building a whole story and an atmosphere around it. Everything is consistent. All the parts are dialoguing with each other.

For each book, another story, another time. And time is indeed the underlying leitmotiv of his works. Not only because he gives new life to something which belongs to the past, but because he is deliberately creating something which will and must reach into the future. His Casket Books are witnessing his love story with Time.

In fact, what is a book if not a bridge connecting different times and spaces and cultures and different minds, distant and far apart from each other? And doesn’t art do the same? Doesn’t art – be it literature, poetry, music or fine arts – always renew itself and become present – even if the work has been made thousands or hundreds of years ago – the very moment you are there in front of it and become an active and indeed necessary part of the artistic process, because you are the one who is reading, or listening or contemplating it hic et nunc, here and now? And, in doing so, at each instant a communication is established between you and the work, and art becomes the language which indeed is. That is the magic, the mystery of art: its living in the realm of an eternal present. And so is knowledge, which is art itself.

Bearing this in mind, Rolla has recently started to add to his Casket Books what he has defined a ‘time capsule’, that is a second but hidden niche, carved inside the very core of the book, which contains one or more smaller works or poems, but which can’t be reached and disclosed unless the book is destroyed. So, you know that something else is there, a hidden treasure nobody will ever see, a mysterious message to be handed down to future generations, yet never to be discovered.

And actually, the Casket Book which he will donate to the winner of the Silver Wyvern Award will be the very first of this kind, thus increasing its value.

Rolla says that he can be even commissioned some personal message to insert into the time capsule, and when the person who will acquire his work will leave it to his or her heirs, that person will know that he can entrust the Casket Book with some meaningful, secret message to his descendants. And yet, nobody will ever know. They might only imagine. Suppose. This way, not only the client will personally contribute to the work in an unique, personal way, but he or she will survive inside the heart of the book. It will be the heirs’ personal choice to tear or not the book apart in order to discover what is hidden inside.

But why must a work within a work, or a personal message remain a secret? Why should the work be destroyed in order to disclose that secret? Well, if we think of art, of any work of art, there will always be some code message which nobody but the artist will ever be able to decipher..

Art is a code language, whose key only the artist knows; and sometimes not even the artist. So powerful is the symbolic essence of that code. I’m of course referring to its ultimate meaning and raison d’etre.

But, for all the others, for us, beyond the critical studies, analysis, exegesis, imagination can compensate for that lack. Because imagination is the source, the fountain of all arts. And, as James Harpur says, the artist drinks at that fountain. And so do we whenever we become that active part of the artistic process. We don’t need to know everything which is involved, we must rather feel, perceive, experience. We must merge into that uninterrupted flow of knowledge and creation and transcendence which art has been since its appearance in human history and become part of it. Then we know. And it is not just a process of our senses – that would be just a superficial perception. It’s something deeper, which involves our entire being, mind, personality, experience. Our soul, that is. Our, in Blake’s terms, innocence and experience. And yet, there will always be some elusive part, something we feel but are unable to grasp, if not in flashes. We will then be able to grasp some tiny sparks of the original Silence beyond the Word. Beyond what Heraclitus calls Logos.

So, if “all arts aim to the word, but the word to silence”, the ultimate goal of poetry, literature, music, visual arts is the holy realm of Silence, is the return to the original source of that fountain from which every inspiration and imagination proceeds.

That is, I think, the meaning of Rolla’s secret, hidden time capsule.

But, what is an Artist’s Book? The following description, offered by the “Poetry Beyond Text Project” could provide a perfect answer to the question:

“Artists’ books are artworks that use the material form of the book as a medium of creative expression. In contrast to fine press printing or illustrated editions, the visual, tactile and aesthetic features of artist’s books are not secondary to their textual content. Indeed, many artists’ books do not contain words but rather work with images, papers, shapes, and folds, to foreground the experience of interacting with the book as an object.”

Johanna Drucker, scholar and renown author of The Century of Artist’s Books, states that Artists’ Books are “the quintessential 20th century art form.” Indeed, the way modern art movements and modern art approach this genre, we could very well say that this is an entirely new form of art, though its roots reach very far back.

According to this perspective, the definition of “book” has become quite nebulous, as Martin Antonetti, president of the Bibliographical Society of America has said. Artists’ Books also offer to artists the unique opportunity of making available and more affordable art to a wider public.

Artists’ Books are not the same as illustrated books. Images are not just inserted into or added to the text in order to illustrate or enrich it, they are not just ornaments, rather they are a true collaboration, an intimate conversation between art and text. An artist’s book is not merely a text where pictures or photos have been added, but it is a creature where text and images and paper and binding and structure form a whole, an inseparable unity.

They are conceived as a whole, they breath together, they are intertwined, they cannot live without each other. In an artist’s book text, images, binding are lovers. We could well say that artists’ books are an aristocratic response to the publishing industry, to mass production extended to what should be culture, to the lack of attention and respect towards knowledge and beauty, reflected in the past by the art of book making. And, in artists’ books, authors, artists and publishers (which are very often one and the same person) can still establish a direct contact with the reader, as their work conveys their love, their passion for their craft, which they share directly – without intermediaries – with the reader.

It is not by chance that artists’ books began to appear in a greater number during the Arts and Crafts movement (just think at the Kelmscott Press founded by William Morris and at the care he took in printing and lavishly decorating his books, like in his Chaucer) when the excellence of technique and the very high quality of materials were on focus. And then with the avant-garde movements, that is during the first and second Industrial Revolution. They reveal a desire of going back to the origin of the book as an art product, when books were expensive, time-consuming, handmade, handwritten and later hand-printed treasures.

The first true artist’s book in this sense and which set the rules for all the others to come was William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience a book he wrote, illustrated, etched, hand-painted, printed, bound and published all by himself with the invaluable help of his devoted wife. He was actually inspired by medieval illuminated manuscripts. Here, the poems are embedded into the pictures and the pictures intertwine and blend with the text. Blake’s illustrations echo back the sounds and the meaning of the verses, at the same time expanding them, emphasizing what, according to Indian aesthetics, is called rasa, a Sanskrit word meaning literally “sap, juice or taste”. It connotes a concept in Indian arts about the aesthetic flavour of any visual, literary or musical work that evokes an emotion or feeling in the reader or audience but cannot be easily described. It refers to the emotional flavors/essence crafted into the work by the author or performer and relished by a ‘sensitive spectator’ or sahṛdaya or one with positive taste and mind. It could be more clearly defined as .a sublimated state of mind, of the poem. In Indian art theory, there are nine main human feelings, or bhavas which generate nine rasas. The rasa theory was first expressed in the Natya Shastra, the main Sanskrit treaty on dramatic art, therefore it was first applied to theatre, poetry, music, dance and then spread to figurative arts. It is a terribly complex system which recalls and widely anticipates the modern depth psychology. I would therefore say that artists’ books are books where texts and images cooperate in generating in the reader those specific rasas the artist intends to evoke. They consider the whole of the book as an art form, or rather as a form in the platonic sense. The platonic idea of the book.

Yet, we can find an earlier example of what can be defined as an artist’s book, in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, in English Poliphilus’ Strife of Love in a Dream or The Dream of Poliphilus. It is a romance said to be by Francesco Colonna. It is possibly the most famous example of an incunabulum. The work was first printed in Venice in 1499 by that genius whose name was Aldo Manuzio and the few original surviving copies are among the rarest and most expensive antique books in the world. This first edition has an elegant page layout, with refined woodcut illustrations in an Early Renaissance style. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili presents a mysterious arcane allegory in which the main character, Poliphilus pursues his love, Polia, through a dreamlike landscape. In the end, he is reconciled with her by the “Fountain of Venus”. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is illustrated with 168 exquisite woodcuts showing the scenery, architectural settings, and some of the characters Poliphilus encounters in his dreams. They depict scenes from Poliphilus’ adventures and the architectural features over which the author rhapsodizes, in a stark and at the same time ornate line art style. And all this integrates perfectly with the type, one of the highest examples of typographic art.

The illustrations are interesting because they shed light on Renaissance man’s taste in the aesthetic qualities of Greek and Roman antiquities. The psychologist Carl Jung admired the book, believing that the dream images anticipated his theory of archetypes and we’ll later see how this book may have inspired Jung’s Red Book. The style of the woodcut illustrations had a great influence on late nineteenth century English illustrators, such as Aubrey Beardsley, Walter Crane, and Robert Anning Bell.

In recent times, artists’ books’ golden age was between the end of the 19th and the first decades of the 20th century. By the end of the 19th century, when the audience for posters and prints by painters began to grow, entrepreneurial publishers began to commission artists to illustrate small editions of books. Some of the first publishers of artists’ books were art dealers who felt that producing books embellished by their artists would increase the audience for their paintings. The French Livers d’artiste were usually books where famous artists contributed to texts of famous poets or writers on invitation of the publishers. Foremost among these visionary publishers was Ambroise Vollard, whose publication of Odilon Redon’s haunting lithographs illustrate Gustave Flaubert’s La Tentation de Saint Antoine (begun in 1896, published in 1938). Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was known for collaborating with avant-garde artists and writers, and his first publication, L’Enchanteur pourrissant (The Rotting Magician, 1909), paired André Derain with the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Albert Skira published Matisse’s first artist’s book, Poésies (1932) by Stéphane Mallarmé, a harmonious matching of seductive linear drawings with Mallarmé’s poetry. Max Ernst and Paul Eluard, collaborated for Eluard’s love poems for Gala illustrated by Ernst. For Klänge Kandinsky wrote the poems and illustrated the book. Picasso illustrated some poems by Eluard La Barre d’Appui, Sonia Delaunay did some gouaches for a book by Blaise Cendrars.

Futurism, Dada, Cubism, Expressionism, Symbolism, Russian avant-garde movements – they all explored and experimented new forms, ideas, techniques and technologies in creating an amazing number of artists’ books of ravishing beauty and artistry. Books, often published in a limited edition or as unique, were now a free space, a new free canvass, to engage upon new possibility of expression.

As in Blake’s masterpiece, often artists have contributed more than images by serving as authors of their own texts. Unlike books in which the artists embellish the words of a writer, these books constitute entire artistic creations, from cover to cover. As for Rolla’s casket books. One early example is Gauguin’s Noa Noa, consisting of writings and woodcuts related to his impressions of Tahiti and the paintings he made there. Of the same year, 1894, is Toulouse-Lautrec’s Yvette Guilbert, first examples of modern books where text and images were conceived as a single object. Where text and image are deeply connected together, like in De Saussure’s notion of the linguistic sign, which is composed of the signifier and the signified.

It is here, at the very core of the intimate interconnection between poetry (intending poetry as any text, which becomes a poem as soon as it becomes part of an artist’s book) and image, that imagination, that is the origin of the creative process, takes place. If we take an artist’s book as a glorious example of the linguistic sign in art, then we will see that image, poetry and imagination are one.

Later, Matisse’s famous Jazz (1947), combines his writings and twenty brilliantly coloured and boldly stencilled compositions, while years later Georg Baselitz’s Malelade (1990) presents archaic folk language and images of animals in forty-one prints.

In the decades since the end of World War II, when American art came to the forefront, there was a similar flourishing of publications, both on art and as art. In the early 1960s, artists’ books—inexpensive booklets and object books usually entirely composed by artists—became major vehicles of artistic creation. With Ruscha’s very famous Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), in which all but one photograph faces a blank page, a new artistic attitude was established. Later, Tatyana Grosman worked with American artists to produce books with unusual formats, like Rauschenberg’s Shades (1964), a book without words printed on sheets of plexiglass. But then there are books shaped as concertinas, with interchangeable pages, books the reader has to assemble in order to read the text, books conceived as sculptures and new technologies employed in visual arts borrowed by the artists’ books genre, etc.

But, what is certain, is that Artists’ Books today are one of the most exciting laboratories in the contemporary art world, where literary texts and visual arts confront each other in an entirely new way, stimulating a new response from the reader, as Martin Antonetti has stated.

This is but a very short survey of the amazing number of wonderful artists’ books produced since the 19th century and I don’t want to annoy you with a longer list. But, before ending my speech, I’d like to mention two immortal masterpieces of the human creative genius and imagination at its highest which may be seen as artists’ books, although they were never intended as such by their creators: the Book of Kells and Carl G. Jung’s Liber Novus or Red Book

Starting from the latter, as perhaps many of you know, in 1913, after his acrimonious break with Freud, Carl Jung fell into a crisis and began to retreat from many of his professional activities, but also many of his energies were withdrawn from the outer world and redirected inwardly.

One day, while he was on a train, he had the vision of a horrible catastrophe with rivers of blood and dead bodies floating all over. A week later, while on that same train, the vision repeated and he also heard a voice saying that all that would become real. At that point, he thought that he was losing his mind and he decided to investigate what was really going on. So he started to provoke waking fantasies and visions and to engage in a dialogue with the characters which emerged. He also wrote down in little black books everything that emerged and painted his powerful visions. He called this activity “active imagination”. Indeed, what he experienced during those years was a journey to hell and back. A diving into his own unconscious to get in touch with his soul. Often he felt he was going to be overwhelmed by a scaring life crisis and that he was in great danger. He even contemplated suicide.

It took him four years to complete this journey into the depths of his Self and then he spent the following years, until 1930, in writing and drawing and painting everything he had seen and discovered in his visions and inner dialogues.

To engage in a very difficult description of the complexities of its content or of the intuitions and revelations Jung had about himself, his soul, his future psychotherapeutic techniques, of the concepts he would develop in his future analytical psychology writings, the role and power of symbols etc. it would be here totally off-topic. What is instead interesting for us now is its form. In fact the huge, heavy, 205 large pages codex, or illuminated manuscript (as this is what indeed is) handwritten on parchment, hand-painted and bound in red leather, was inspired not only by the numinous images which had burst forth from his unconscious, but, for the form he chose to organize them, also by similar medieval works, like the Book of Kells he kept in mind, and Blake’s Songs of Innocence, the Hypnerotomachia Poliphyli, while he perceived his inner journey to be similar to Dante’s Comedy and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra.

In The Red Book he wrote: “I speak through images … In fact I could not express in any other way the words emerging from the depth.”

The absolute, total interdependence of text and painted images, of decorations, illuminated initials, symbolic use of colours, page structure and conception recalls medieval illuminated manuscripts, which Jung knew and had thoroughly explored. You can’t separate the text from the illustrations, as the one clarifies and comments the others and vice versa. The Red Book, as he had called it, is a book of visions, as it all started from that first terrible, scary vision in 1913 and then many others followed. But then, from those significant, numinous visions words poured out, which explained them and integrated them into his consciousness.

As the Austrian art theorist Konrad Fiedler stated, art is a process from chaos to clarity, from confusion to order. It took to Jung more than 15 years to see and write and paint his Red Book, although he left it unfinished. To give an order to all that overwhelming material that was surfacing and threatening him. And then it took him the rest of his life to integrate and elaborate all that material. The blindingly magnetic, archaic and mysterious beauty of its pages, of its colours, of its mesmerizing illustrations triggers powerful feelings and stirs our imagination. To Jung, they were that very process so clearly described by Fiedler. In the Red Book art becomes a means and instrument of knowledge and inspiration.

The Red Book is a map not only of Jung’s unconscious and a journey into it, but of the collective unconscious as well, a concept he actually formulated and developed during the composition of this book. Jung’s artistic and calligraphic skills played a great role in rendering his visions and in writing down his prophetic texts. May we consider it as an artist’s book? “All my works, all my creative activity,” he would recall later, “has come from those initial fantasies and dreams.” Yes, he drank at the source of imagination, at that aforementioned fountain, in search of what he called the “Spirit of the depth”, as opposed to the spirit of the time, which had so deluded and betrayed him before this devastating yet renewing crisis hit him.

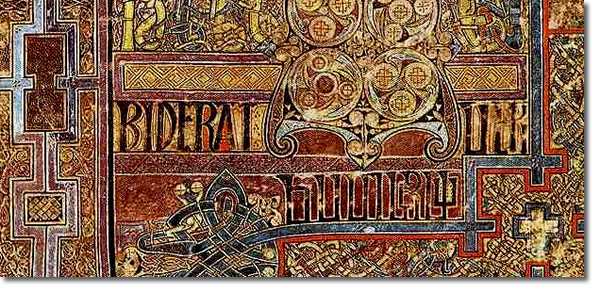

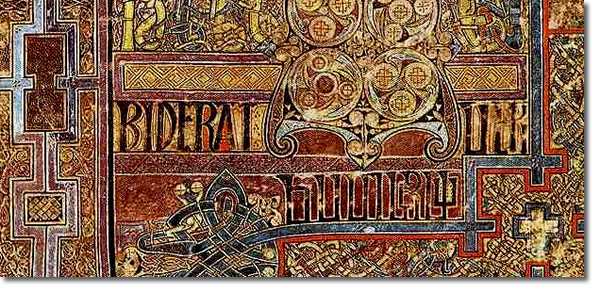

And now, at the end, let’s go back to the beginning. The Book of Kells. James Joyce wrote to a friend: “It is the most purely Irish thing we have, and some of the big initial letters which swing right across a page have the essential quality of a chapter of Ulysses. Indeed, you can compare much of my work to the intricate illuminations.”

James Harpur, who has just released his last collection of poems, The White Silhouette, whose central section features his final version of his long, four parts poem Kells, (he has worked at it for more than fifteen years) on a RTÉ radio interview said that the first time he saw the Chi Rho page, it was like someone had dropped a match in a box of fireworks and frozen the resulting explosion. Well, doesn’t this image recall the original Big Bang? For Harpur the Book of Kells is the materialization of the soul of Ireland, its pages holding the cultural and spiritual DNA of the country.

Indeed, the impression one immediately gets is that words are totally merged into images and images become words. The intricacies, the snakelike convolutions of the lines, the tremendous complexity of the patterns, remind of a brain as much as of clusters of galaxies, endlessly rotating around themselves and around each other. Each line affects all the others, each colour operates a transformation over the other colours, as if everything were alive, and this alchemic transformation forms a continuum in time and space, it is a non-stop process, taking place right under your eyes. Even figures, architectural structures become abstract elements, become parts of this flowing current of forms and colours. Everything is speaking with the power of symbols. There are no boundaries, no distinctions to separate thought and vision, words and images. Thus, mirroring and reproducing through images the sacred Word embedded into the illuminations, which breaths through them.

The Book of Kells’ illuminations remind me of quantum physics. Although, alas, I’m terribly ignorant about this subject, I think one could recognize, in the overall conception of the Book, some of its fundamental principles, like the fact that everything is made of waves, also particles, and that quantum physics is about the very small.

Although some of the Book of Kells illustrations are rigorous architectural structures, like the Eusebian Canons tables, and there are full page images of the Evangelists, of the Virgin with Child and of Christ, a good part of the decoration is carried out in the intricate insular style, invading frames, empty spaces, and almost self-generating. The impression is that of a space brimming and pulsating with a wavelike energy. The sacred Word emanating from God is not only written on the vellum, but can be visualized as the image of the created universe.

As Carl Nordenfalk says: “the initials … are conceived as elastic forms expanding and contracting with a pulsating rhythm. The kinetic energy of their contours escapes into freely drawn appendices, a spiral line which in turn generates new curvilinear motifs…”.

Also, the intricate paths of the lines, separating themselves and constantly bifurcating, abruptly taking different directions leading to different aspect of reality, remind of Hugh Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics, according to which every event is a branch point; so, in Everett’s reading, the Schroedinger cat theorem gives that the cat is both alive and dead, even before the box is opened, but the “alive” and “dead” cats are in different branches of the universe, both of which are equally real, but which do not interact with each other.

Quantum physics is about the very small. Well, if we analyze the amazing details of the illuminations, we will soon realize that many of the largest images, or their frames and decorations are composed of millions of lines, motifs, knots, tangles, sometimes so tiny – and yet so amazingly perfect – that they can be seen only through a magnifying glass. There weren’t magnifying glasses at the time, so it still remains a mystery how they did it. And this was perhaps the reason why Gerald of Wales reports that the Book of Kells had been written by the angels.

The anonymous illuminators and scribes who created the Book of Kells had this in mind: to make visible the invisible, to infuse spirit into matter, to make eternal what was transient, to express the ineffable through forms and colours, so that the divine energy could be transformed into matter and matter into divine energy. A spiritual version of the Relativity theory made visible.

FRANCESCA DIANO

Copyright© by Francesca Diano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Commenti recenti