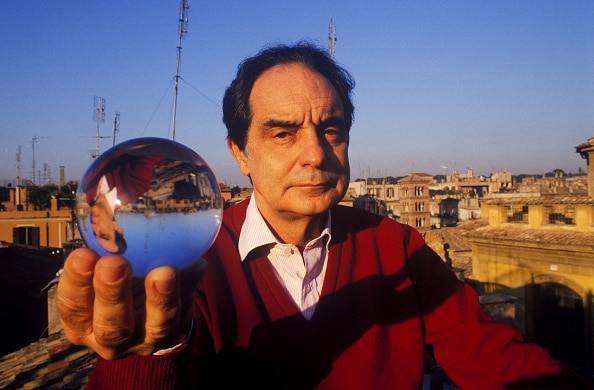

Foto di © Dino Ignani

James Harpur San Simeone Stilita, testo a fronte, a cura di Francesca Diano, Proget Edizioni, 2017

In occasione della presenza in Italia di James Harpur, a fine maggio 2017, che ha tenuto, per la prima volta nel nostro paese, una serie di incontri e conferenze, esce l’elegante plaquette con il lungo poemetto in quattro parti San Simeone Stilita, edito da Proget Edizioni e da me curato. Insieme a questo testo, sto lavorando alla ricca antologia Il vento e la creta – selected poems, 1993 – 2016, che raccoglie testi scelti dalle otto raccolte fino ad ora pubblicate e alcuni testi in prosa. James Harpur, un poeta ormai considerato fra i maggiori del nostro tempo a livello internazionale, ma che, in Italia, non ha ancora la fama che merita.

Il poemetto di circa 600 versi, è dedicato alla bizzarra, affascinante figura di San Simeone Stilita. Ne propongo qui la prima parte, con un breve estratto del mio testo introduttivo.

F.D.

***************

“La via in su e la via in giù sono una e la medesima”[1]. E veramente il basamento della colonna da cui clama lo Stilita di James Harpur potrebbe recare incise le parole di Eraclito, poiché quella colonna, che vorrebbe essere una verticale via di fuga dal mondo, ma si rivela vano, illusorio abbaglio, non è vettore unidirezionale verso l’invisibile – ascesa dall’umano al divino, dalla materia allo spirito – ma percorso inverso, anche, dal divino all’umano, ed è, allo stesso tempo, via orizzontale ché, nella tensione che tra quelle polarità si crea, vibra, e questa vibrazione ne dissolve i contorni, fino a sfarli in un alone luminescente. Una vibrazione che si dilata, in onde centrifughe, ad abbracciare lo spazio circostante, permeandolo, inglobandolo.

Fu questa, forse, l’origine dell’attrazione magnetica che colonna e Stilita, non separabile binomio, esercitarono allora, seguitarono ad esercitare dopo la sua morte, ed esercitano, se la sua particolare forma di fuga dal mondo ebbe più di un centinaio di imitatori, ancora fino a metà del XIX secolo, mentre Alfred Tennyson scrisse un poemetto di duecento versi – in realtà assai critico e ironico – sull’anacoreta e Luis Buñuel, nel 1964, girò un film, Simòn del desierto, Leone d’argento alla Mostra del Cinema di Venezia. In entrambi, l’immagine di Simeone è ambigua e contraddittoria; ma questo non deve meravigliare, ché ambiguo e contraddittorio è il rapporto di Simeone con sé stesso, col proprio Dio e con le sue creature.

La colonna, fuga e piedistallo, da lui scelta come distacco-separazione dal mondo e come diretta via d’accesso all’invisibile, è essa stessa contraddizione, anzi, è un paradosso. In fondo non è che un supporto di pochi metri; nulla rispetto all’immensa distanza – non certo solo fisica – fra terra e cielo. Così il Simeone di Harpur anela negando, rifiuta ciò di cui ha sete, cieco di fronte all’essenza stessa di quanto desidera, s’illude di non dover fare i conti col mondo cui appartiene. A tal punto vi appartiene, da sentirsi costretto a operare una rimozione, un’escissione cruenta, di cui parla in termini chirurgici.

Per quanto Simeone si allontani dalla terra, dalla materia che ricusa con tutto l’essere, per quanta distanza ponga tra sé e la realtà, per quanto tenti, accrescendo sempre più l’altezza del suo trampolino, di farsi possessione di Dio oltre un cielo, per lui, deserto quanto il deserto di rocce e sabbia, lo Stilita è prigioniero di un inganno, di un feroce equivoco. E più Simeone nega il suo corpo (parte di quel mondo fisico da cui fugge), più quel corpo esercita una furiosa attrazione sui suoi seguaci. Il suo occhio, che rifiuta di abbracciare la sfera dell’evento per perdersi in quella della forma, se ne stacca e si solleva verso il vuoto, cercando risposta a una domanda improponibile. La crudeltà del suo auto-inganno è tanto più corrosiva, quanto più Simeone trascura l’impossibilità di eliminare uno dei due poli, la tensione dai quali è generata è la vita stessa. Il Simeone di Harpur non vede, se non alla fine, che la sua colonna è inutile; il cielo è qui, Dio è qui, su quella terra che lui si rifiuta di sfiorare, in mezzo a quell’umanità da cui fugge. Inseguito.

Non si dà forma senza evento, né evento senza forma. Non si accede al divino se non passando attraverso l’uomo. Né si accede all’uomo senza fare i conti col Sacro. L’evento primario, per ogni cristiano, è Cristo incarnato. Tu neghi la carne, neghi l’uomo, e neghi Cristo, ne fai una favoletta. Trascendere è possibile solo a condizione di accettare questa verità, e difatti, in tutto il testo, mai Simeone si rivolge altri che a Dio; solo negli ultimi tre versi, dopo l’avvenuta catarsi, nomina Cristo:

Ciascuno è Cristo

Che solo cammina fra campi di grano

O lungo il mare della Galilea.

Solo. La visione che Simeone ha dell’uomo è finalmente quella di Cristo. Solo, ma non separato. Cristo è nella relazione che dell’umanità fa una. È quella relazione. Simeone lo comprende infine quando l’amore di coloro che lo soccorrono e lo riportano in vita, dopo la quasi-morte, cui come giudice spietato si autocondanna, gli rivela da quale profonda tenebra originasse il suo errore, quando, superato il proprio abbaglio, riconosce negli altri, e dunque in sé, il miracolo, sì abbagliante, dell’incarnazione. Abbandonare l’umano per tornare all’umano, dunque.

La via in su e la via in giù sono una e la medesima. Dio, o il Sacro, come lo si intraveda, se mai lo si intravede, non è tenebra, ma è attraversando la tenebra di sé stessi che, nel cercarlo, solamente lo si può trovare, per attitudine o illuminazione. Non è fuori di noi, è in noi.

La piattaforma su cui Simeone visse era di forma quadrata (“la quadrata materia”); il simbolismo numerologico del Quattro, sia come manifestazione di tutto ciò che è concreto e immutabile, sia come manifestazione della materia, dell’ordine, dell’orientamento, torna in tutto il poemetto, a partire dalla sua stessa struttura quadripartita. A significare che la salvezza è in questo mondo, in questa realtà, nell’abbracciare la propria umanità.

[…….] Storicamente, quel corpo che lui aveva negato, dopo la morte scatenò aspre rivalità – vere guerre fra gruppi armati – per il suo possesso. Così, l’originaria negazione del corpo, ne sancisce infine, con ironico rovesciamento, la sacralità, ne fa oggetto di venerazione, facendo del cadavere centro di culto straordinario.

Il corpo fu trasportato ad Antiochia ed esposto per trenta giorni nella chiesa di Cassiano e, successivamente, traslato nel duomo ottagonale costruito da Costantino. L’ottagono, non si dimentichi, è simbolo di resurrezione. Non è chiaro, dai testi, se il corpo o parte di esso, fosse poi portato a Costantinopoli. Nel VII secolo però, con la caduta di Antiochia in mani arabe, di quel corpo si perse ogni traccia.

Quel che invece rimase, come sede di culto vivissimo, fu il luogo ove sorgeva la sua colonna, a Telanissos (ora Qalat Siman, nell’attuale Turchia), e dove sorse un enorme monastero e una grande basilica, di cui oggi restano rovine. Notizie, chiaramente gonfiate ad arte, riportano che la chiesa potesse contenere fino a diecimila persone. Numero che semplicemente indica una grande pluralità indefinita, (penso all’uso di tale numero nella tradizione letteraria e filosofica cinese) ma attesta l’eccezionalità del culto.

[…..]

Francesca Diano

[1] Eraclito, I frammenti e le testimonianze, a cura di Carlo Diano. Fondazione Lorenzo Valla.

Foto di © Dino Ignani

Da

SAN SIMEONE STILITA

Traduzione di Francesca Diano

“Si collocò su di una serie di colonne dove trascorse il resto

della vita. La prima era alta poco meno di tre metri e su

di essa visse quattro anni. La seconda era alta circa cinque

metri e mezzo (tre anni). La terza, di dieci metri, fu la sua casa

per dieci anni, mentre la quarta ed ultima… era alta diciotto

metri. Lì visse per gli ultimi vent’anni della sua vita.”

Oxford Dictionary of the Saints

“Non c’è bisogno di graticole; l’inferno sono gli altri.”

Jean-Paul Sartre

“Ovunque io voli è Inferno; io stesso sono Inferno…”

Milton, Paradiso perduto, IV, 75.

1

Nell’urto del calore,

Tremano gli orizzonti di chiarità fumosa.

Il deserto è un fondale marino

Da cui tutta l’acqua sia riarsa.

Qui non ebbe potenza la creazione

Se non per sabbia, rocce,

Ciuffi d’erba e pidocchi.

Un arco di montagne, vetrose di calore,

Isola questo paradiso adamantino

Dalla profanazione del triviale.

Ho tutto il giorno per volgermi

In direzione dei punti cardinali

In armonia col sole

Osservare il vuoto che m’assedia,

Sabbia che avanza e mai sembra muoversi,

L’armata del non-essere

Che con la notte si dilegua nel nulla.

Sono il centro di un cosmo

Acceso solamente dai miei occhi.

Sono la meridiana del Signore:

La mia ombra è il tempo

Ch’egli proietta dall’eternità.

La notte facevo questo sogno:

Mi trovo a scavare in un deserto

Come scorpione in fuga dal calore;

la buca si fa così ampia e profonda

Che sono chiuso, come in un pozzo,

E sfiorato da un’ombra rinfrescante.

Ogni vangata di sabbia a espellere un peccato

Alleggerisce l’anima dall’oppressione

E illumina il mio corpo dall’interno

Ma mi fa scorgere più buio giù nel fondo

E seguito a scavare

Finché mi sveglio, colgo la luce del giorno.

Con il tempo compresi

Che questo era un sogno capovolto:

Avevo costruito un buco speculare

Ma fatto materiale da blocchi di pietra.

Qui, sulla cima, son mio proprio signore,

Il mio palazzo è una piattaforma balaustrata

Il tetto un baldacchino di sconfinato azzurro,

I terreni di caccia sono un mare di polvere.

Non odo altra voce che la mia,

A profferire anatemi, preghiere – pur solo

Per ricordare il suono,

O mi sussurra in testa, dove evoco

I chiacchierii di Antiochia

Gerusalemme e Damasco,

Di eremiti che ciarlano sui monti.

Signore, è eresia pensare

Che l’isolarsi spiani la via verso di te,

Che la gente sia corrotta ed infetta

Poiché calpesta quiete, silenzio, solitudine

Nel suo accapigliarsi per dar sollievo

Ai tormenti dell’imperfezione?

Quando alla terra ero vincolato, un penitente

Incatenato a una cornice di roccia

Non riuscivo a pregare se non pregando

Che la notte si potesse protrarre

Contro l’onda dell’alba che s’infrangeva

Contro la roccia, rivelando pastorelli

Sboccati, che scagliavano pietre,

E plebaglia di pellegrini

Che passavano da un oracolo all’altro

Condotti senza posa da domande

Lasciate prive di risposta

Per dare un senso alla vita

E far fare esercizio alle gambe.

Perdonami Signore –

Credo di odiare il mio vicino.

Pur se appartengo al mondo

Ora almeno la superficie non la tocco.

So che odio me stesso,

Della vita temo le dita che contaminano,

Pavento gli effluvi del giorno

Sguscianti attraverso sensi incontrollati

Per putrefarsi dentro la mia testa;

Con codardia crescente

Temo l’attaccamento dell’amore

Temo l’infinità della morte

Temo il sonno, l’oscurità, i dèmoni

Striscianti, i loro occhi grigi come pietra.

Lo so che devo rendere me stesso

Un deserto, un vaso ben lustrato,

Perché in me tu riversi il tuo amore

E trasformi in luce la mia carne.

La notte invece sogni immondi

Mi colmano di donne che conobbi –

Ma un po’ mutate e nude –

Che danzando tra velami di sonno

Sussurrano alla mia verginità.

Si dice che simile attrae simile.

Quanto putrido devo essere dentro

Se di continuo mi pasco

D’ira, lussuria, rancori del passato

Rievocando in crudele dettaglio

Involontarie offese che punsero il mio orgoglio,

Lasciando che la vendetta cresca

Con una tale grottesca intensità

Che la bile potrebbe intossicare l’esercito persiano.

Quasi sempre mi sento dilaniato.

Uno spirito che anela alla luce,

E un corpo con colpevoli appetiti

Che domo stando rigido e ritto tutto il giorno,

Osservando la sagoma emaciata

Ruotarmi lenta intorno

In attesa di debolezza, esitazione.

Oppongo la volontà contro la carne

Ma quando il sole viene inghiottito

Mi unisco al buio, ombra mi faccio

Nell’anarchia sudicia dei sogni;

Inerme, alla deriva, tutta notte mi volvo

Attorno alla rammemorante colonna dei miei peccati.

All’alba mi risveglio, avido di provare la letizia

Di Noè che libero galleggia verso

Un mondo incontaminato risplendente,

Ma quando il sole irrompe

Sono un corvo malconcio in un nido

Di sabbia, capelli, feci albe

E croste di pane che un monaco babbeo

Mi lancia insieme a otri –

Un essere senz’ali che sogna di volare

Sento il deserto che mi stipa dentro

Ogni solitudine io abbia mai provato.

Le distese di nulla del deserto

Specchi giganti dell’anima mia

Riflettono ogni frammento di peccato;

Più mi purifico

Più emergono macchie brulicando

Come formiche che schiaccio adirato –

Come può Dio amare la mia carne rattrappita,

La mia fragilità, l’assenza di costanza?

Perché attende per annientarmi?

Mille volte mi inchino ogni giorno –

La notte resto desto a pregare

E prego per star desto.

A volte mi domando s’io preghi

Per tenere il Signore a distanza.

ST SYMEON STYLITES

by

JAMES HARPUR

From

The Dark Age

2007

“He set himself up on a series of pillars where

he spent the remainder of his life. The first one

was about nine feet high, where he lived for four years.

The second was eighteen feet high (three years).

The third, thirty-three feet high, was his home for

ten years, while the fourth and last … was sixty feet

high. Here he lived for the last twenty years of his life.”

OXFORD DICTIONARY OF SAINTS

“No need of a gridiron. Hell it’s other people.”

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

“Which way I fly is Hell; my self is Hell…”

MILTON, PARADISE LOST, IV.75

1

Heat struck,

Horizons wobble with clarified smoke.

The desert is a sea-bed

From which all water has been burnt.

Creation, here, was impotent

Except in sand, rock,

Spikes of grass, and head lice.

A sweep of mountains, heat glazed,

Cuts off this adamantine paradise

From profanities of the vulgar.

I have all day to turn

Towards the compass points

In rhythm with the sun

And watch the emptiness besiege me,

Advancing sand that never seems to move,

An army of nothingness

Melting away to nothing with the night.

I am the centre of a cosmos

Lit only by my eyes.

I am the sundial of the Lord:

My shadow is the time

He casts from eternity.

I used to have this dream at night:

I’m in a desert digging

Like a scorpion escaping heat;

The hole becomes so wide and deep

That I’m enclosed, as if inside a well,

And lightly touched by cooling shade.

Each spade of sand expels a sin

Relieves the pressure on my soul

And lights my body from within

But makes me see more dark below.

And so I keep on digging

Until I wake and grasp the light of day.

In time I came to realize

The dream was upside-down:

I built a mirror hole

But made material with blocks of stone.

Here, on top, I rule myself,

My palace a balustraded stage

Its roof a canopy of endless blue,

My hunting grounds a sea of dust.

I hear no voice except my own,

Exclaiming curses, prayers – if only

To remind itself of sound,

Or whispering in my head, where I revive

The chatterings of Antioch

Damascus and Jerusalem,

Of hermits gossiping in mountains.

Lord, is it heresy to think

That isolation smoothes the path to you,

That people are infectiously corrupt

Trampling silence, stillness, solitude

In their scramble to relieve

The agony of imperfection?

When I was earthbound, a penitent

Chained up on a mountain ledge

I could not pray except to pray

For night to be protracted

Against the wave of dawn that broke

Against the rock, unveiling shepherds boys

Foul-mouthed, throwing stones,

And ragtag pilgrims

Drifting from oracle to oracle

Led on and on by questions

They kept unanswered

To give their lives a meaning

Their legs some exercise.

Forgive me Lord –

I think I hate my neighbour.

I may be of the world

But now at least I do not touch its surface.

I know I hate myself,

Fearful of life’s contaminating fingers,

Dreading the day’s effluvia

That slip through each unguarded sense

To rot inside my head;

More and more I’m cowardly

Afraid of love’s attachments

Afraid of death’s infinity

Afraid of sleep, darkness, demons

Scuttling, their eyes as grey as stone.

I know I have to make myself

Into a desert, a vessel scoured,

For you to pour your love in me

And turn my flesh to light.

Instead at night foul dreams

Fill me with women I once knew –

But slightly rearranged and naked –

Who dance through veils of sleep

Whispering to my virginity.

It’s said that like draws like.

How putrid I must be inside

That I’m forever feasting on

Anger, lust, spite from years ago

Recalling in excruciating detail

Unwitting slights that pricked my pride,

And letting vengeance grow

With such grotesque intensity

The bile would poison all the Persian army.

Most days I think I’m split in two.

A spirit yearning for the light

And a body of delinquent appetites

I tame by standing stiff all day,

Watching its scraggy silhouette

Revolve around me slowly

Waiting for hesitation, weakness.

I set my will against my flesh

But when the sun is swallowed up

I join the dark, become a shade

Within the filthy anarchy of dreams;

Helpless, adrift, I’m turned nightlong

Around the memory column of my sins.

At dawn I wake, bursting to feel the joy

Of Noah floating free towards

A shining uncontaminated world.

But when the sun erupts

I am a tatty raven in a nest

Of sand, hair, albino faeces

And bread rinds a half-wit monk

Lobs up to me with water-skins –

A wingless creature dreaming of flight

Feeling the desert cram inside me

Every loneliness I’ve ever known.

The desert’s fields of nothing

Are giant mirrors of my soul

Reflecting every scrap of sin;

The more I purge myself

The more the specks crawl out

Like ants I stamp to death in rage –

How can God love my shrinking flesh,

My frailty, lack of constancy?

Why does he wait to strike me down?

I bow a thousand times a day –

At night I stay awake to pray

And pray to stay awake.

Sometimes I wonder if I pray

To keep the Lord away?

© by James Harpur, 2007 e Francesca Diano 2017. RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA

Commenti recenti